This story feels hardly unique among queer people who have had to make their way in unfriendly spaces. My college roommate and I attended a homophobic Christian institution, that would really rather us not be there.

We came out to each other over Facebook Messenger. We had met on the incoming freshman page, and I had sent her a message to just say hello and get to know her. Within a few hours, we were both out to each other as bi and had decided to be roommates. We remained roommates all four years and I’ll be in the wedding party when she gets married this fall.

We did our best to leave our college better than we found it. By sophomore year I was treasurer of Queer and Allies (Q&A) and later became president my junior and senior years. I got to do a lot of things to make the school safer for queer people, and there was a lot more I could have done.

When I first joined Q&A it was small and under programmed. It felt both relieving and underwhelming to have this community. That wasn’t the fault of the club leaders at the time, there just hadn’t been a good infrastructure for the club yet.

Eventually, though, we started growing.

Queer & Allies: our pocket of queer

Word got around more and more queer people and our allies kept showing up.

We started doing all kinds of fun things; trips to Six Flags, craft times, game nights, queer dinner parties, and a trans 101 event for the staff. All of these were added to the exciting events the group had already had. Suddenly it became about something more than just holding on, it became about queer joy. It was a space for full authenticity.

We had difficult conversations and worked through hard times, but we also had a lot of fun.

Queer joy is something that is in short supply in queer media. The amount of queer movies where nobody dies at the end is slim. And even then, most stories are about queer trauma: bad coming out stories, the AIDS crisis, and the aftermath of hate crimes or inequitable policy decisions.

I’m not saying there isn’t media out there that celebrates queerness, I'm just saying it seems the only way straight people care about us in Media is when we’re being traumatized.

To have this space carved out simply for joy was a life-changing experience. To be able to go ride a roller coaster at Six Flags knowing the only people at the park that night were queer people and our allies was something both joyful and comforting. To do simple crafts while having casual, easy, conversation is something hard to come by in communal settings. I got a lot of friends simply by hanging out and being my full authentic self without needing my defenses up.

It wasn’t all fun and games, however.

This was an unsafe space, after all

In the second semester of my sophomore year, our campus pastor was removed from her job for officiating a wedding between two men. Anger erupted everywhere and not all on our side.

Some were angry at her for doing this, others were angry that the school and Church denomination would remove her. It was a torrent of terrible on all sides and queer people were caught in the middle.

It was one of the most isolating times of my life, and the closest I ever came to transferring or dropping out. We pushed through as a community, but it was not an experience I ever want to live through again.

When people learn about this, I get asked a lot of questions about why I would go to a school like that, or why I would stay at a school like that, and usually, I just say “the theatre program”, or “the scholarship money”.

Neither of those are untrue, but I do feel like that isn’t the full answer. The real answer is more complicated than a five-minute conversation can convey.

Why we hang on in the queer community and why we fight

There are queer people everywhere. We exist in all industries and cities. But not every space is safe for us to exist and to exist joyfully. Sometimes, the answer to why we stay is that we have nowhere else to go. Sometimes the answer is that despite the failings and evils of the institution, we have people there who can’t come with us and we can’t leave behind. And sometimes, the answer is because we have a chance to build something safe here, at least for a while.

Queer people have been targeted for generations. Branded with pink triangles, arrested and tortured with forced castration, or sent to endure the evils of conversion therapy. Our world has been a constant of being unsafe, so asking why we remain in unsafe places is really the wrong question.

Where are the safe places? Few exist, though there are tiny pockets of rest and queer joy, but not enough, and not often enough. It makes sense that instead of leaving, we stay and defend our corner of queer joy. We defend our queer joy and know that not everyone has the luxury to escape and that sometimes you are forced to make do with where you are. It’s because of this that queer people tend to find each other quickly and cling to each other once we are found.

There’s a lot of people I found in my time at school that I will cherish forever. People like my roommate, my co-leaders of Q&A, group members, or people who never came to meetings but supported us in other ways. Allies who came to bat when we asked them to. All the people who understood that safe spaces are hard to come by and that sometimes you have to carve them out yourself.

Queer coding: the art of finding each other in unsafe spaces

Being queer in a world stacked against you is exhausting, especially when trying to make a safe space for yourself. Because of the exhaustive nature of existing under oppression, queer people find each other and hold on for dear life. We find each other through a number of ways for a number of reasons. A lot of queer people seek out specific communities like the group I ran because we try to make ourselves easy to find. Other queer people find each other by subtle queer coding that signals safety.

Queer coding has been around since the beginning as a way for queer people to communicate directly under the eyes of those around us. If while reading the next few paragraphs, you somehow don’t believe queer coding exists, I dare you to look up the Subaru lesbian marketing campaign, those Zelda license plates weren’t accidental.

While queer coding has been around for a long time, it was coined as a phrase in 1995.

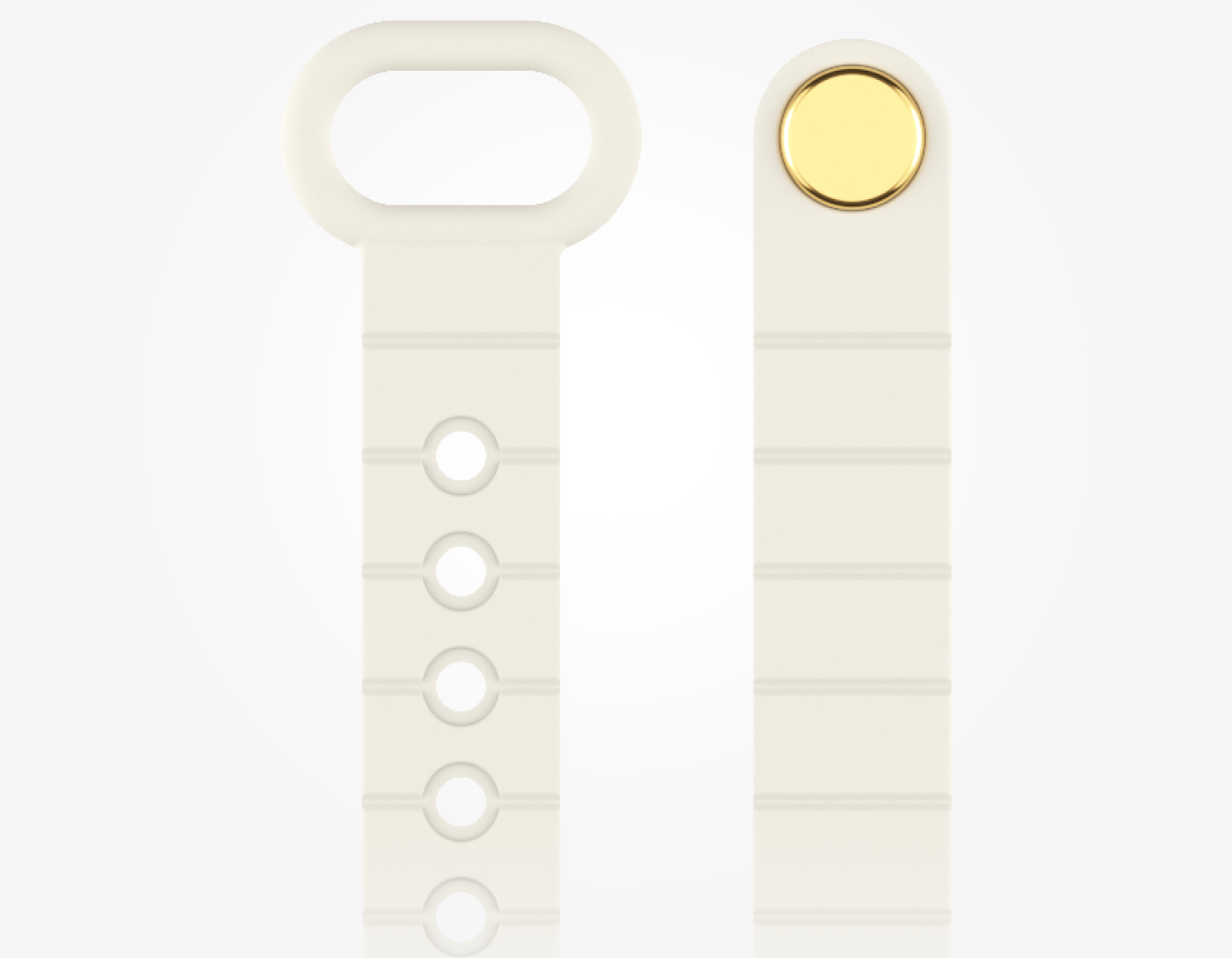

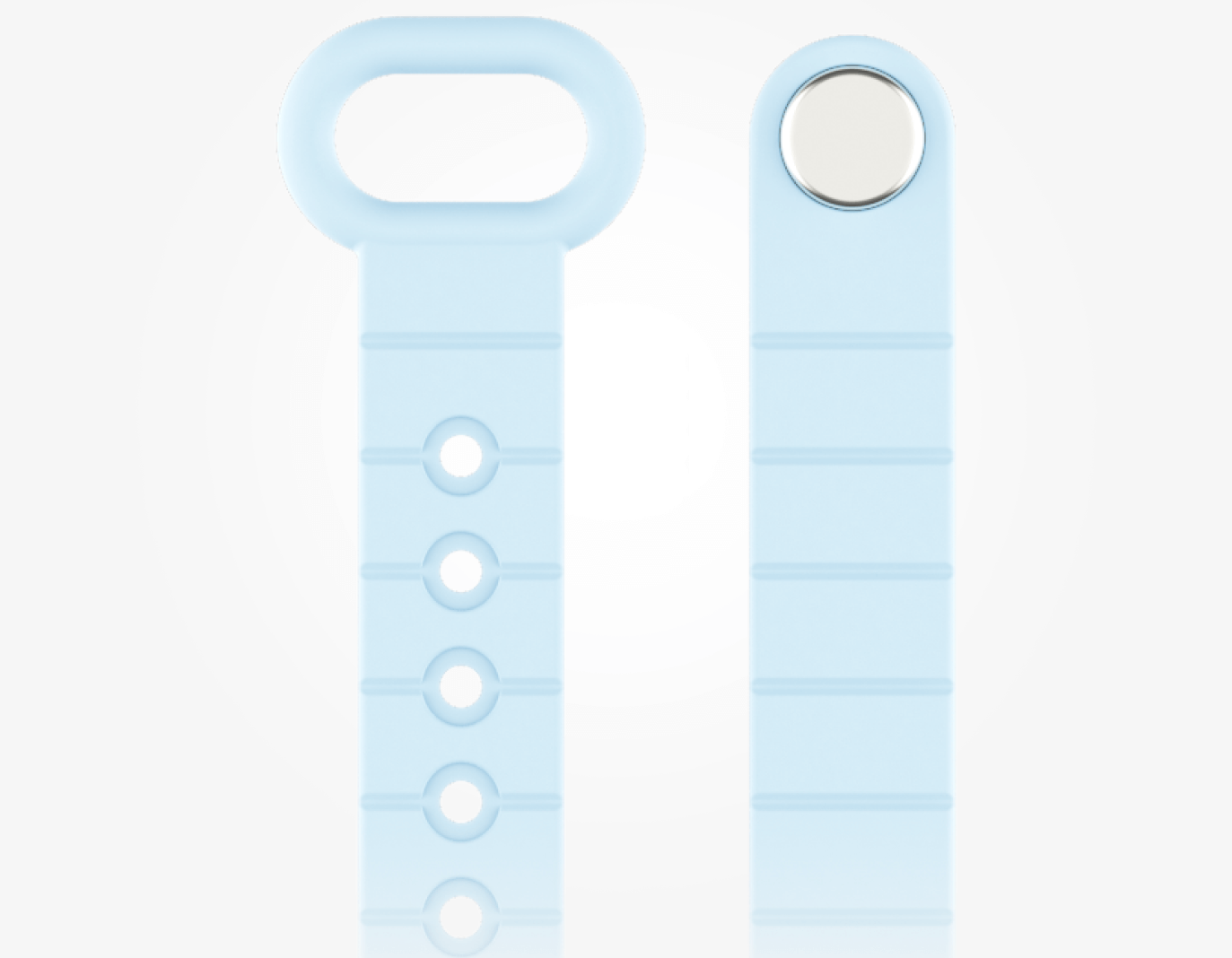

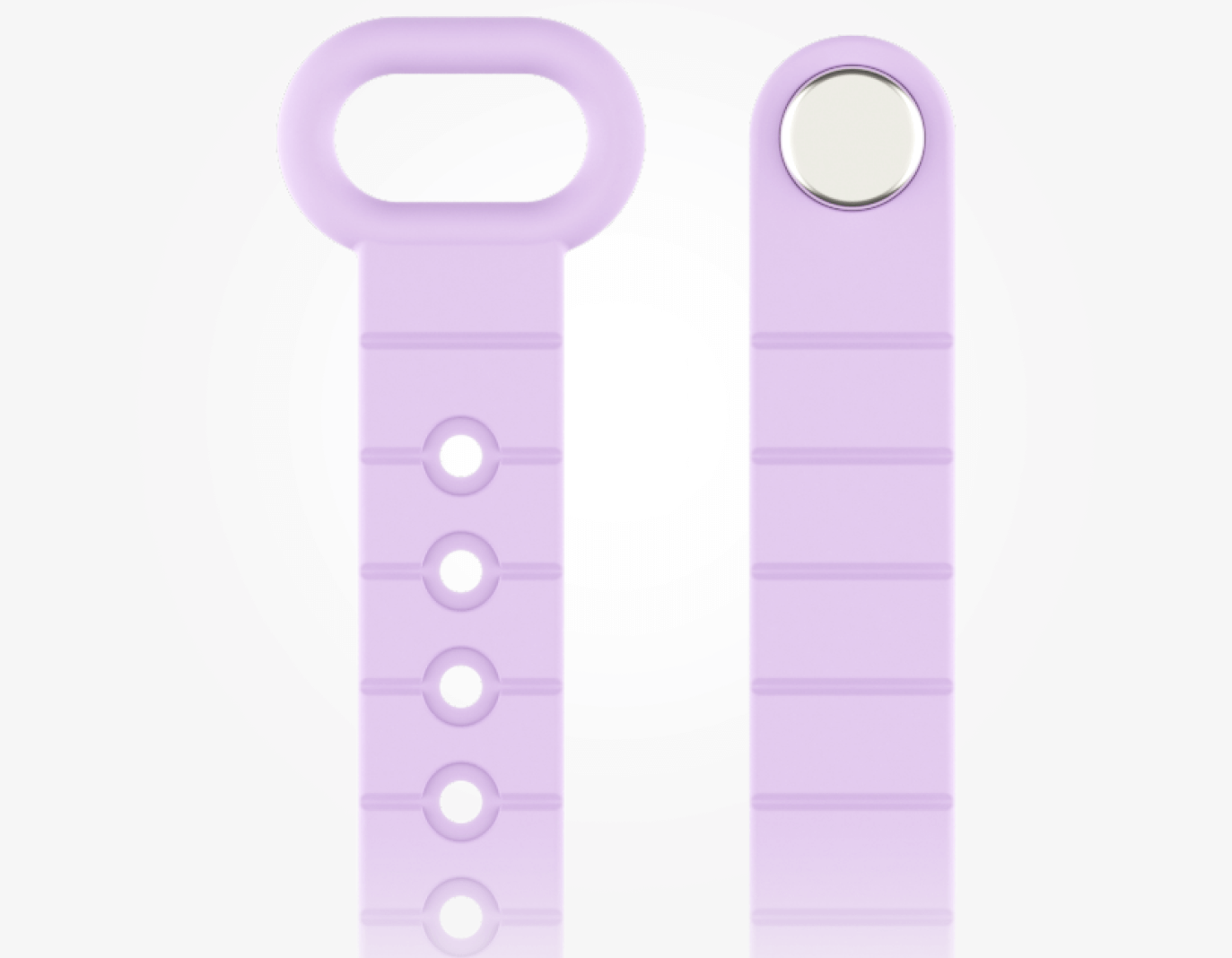

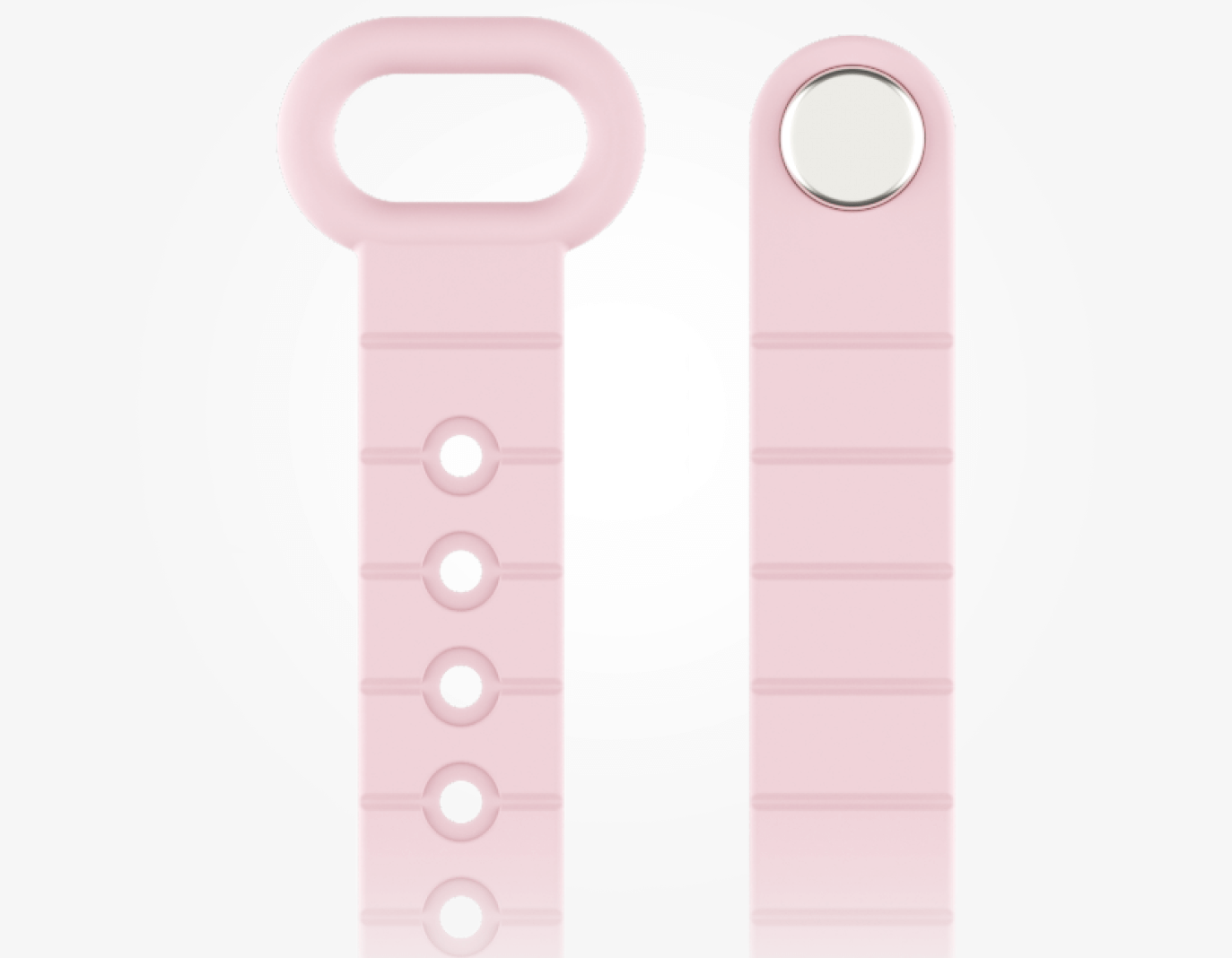

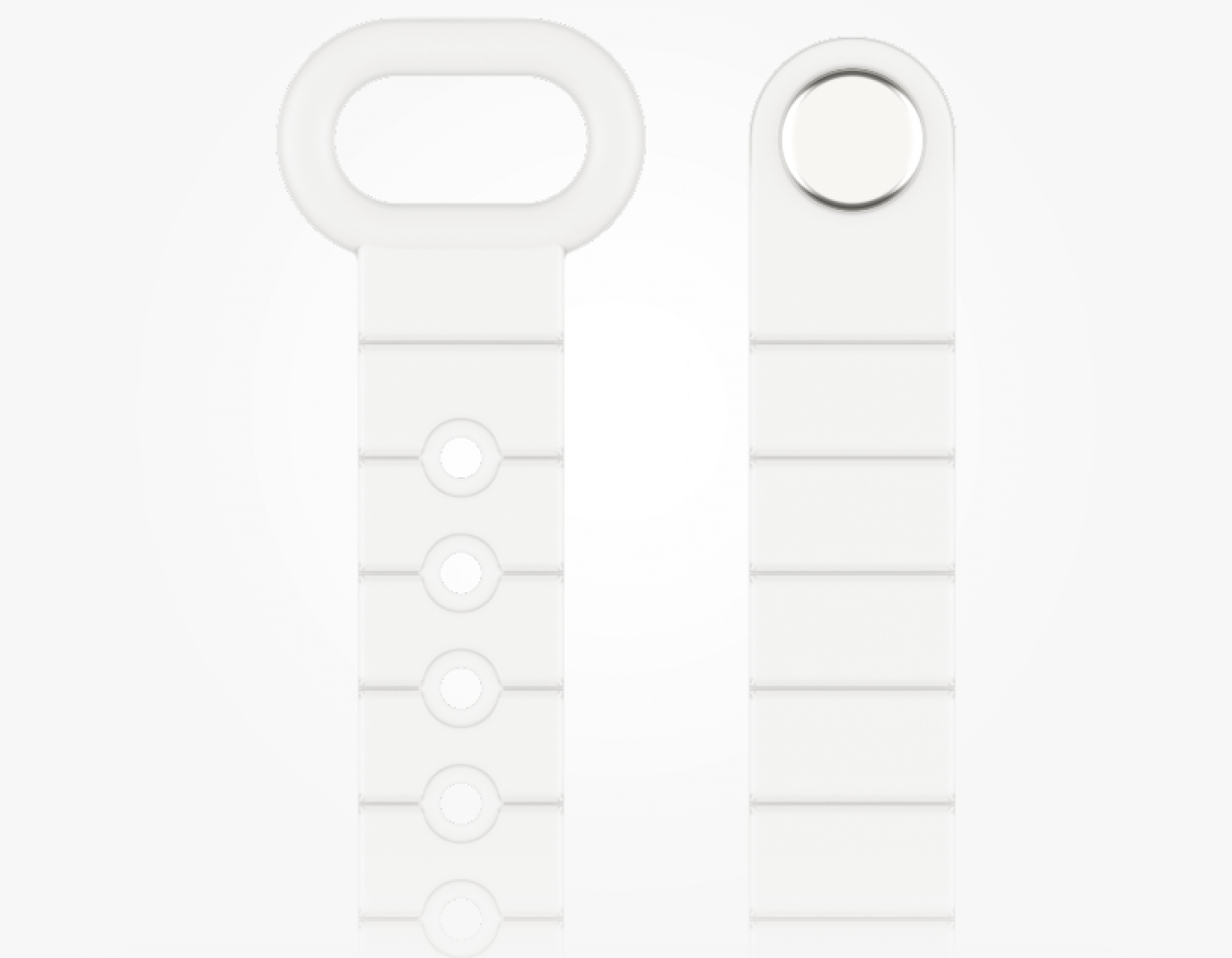

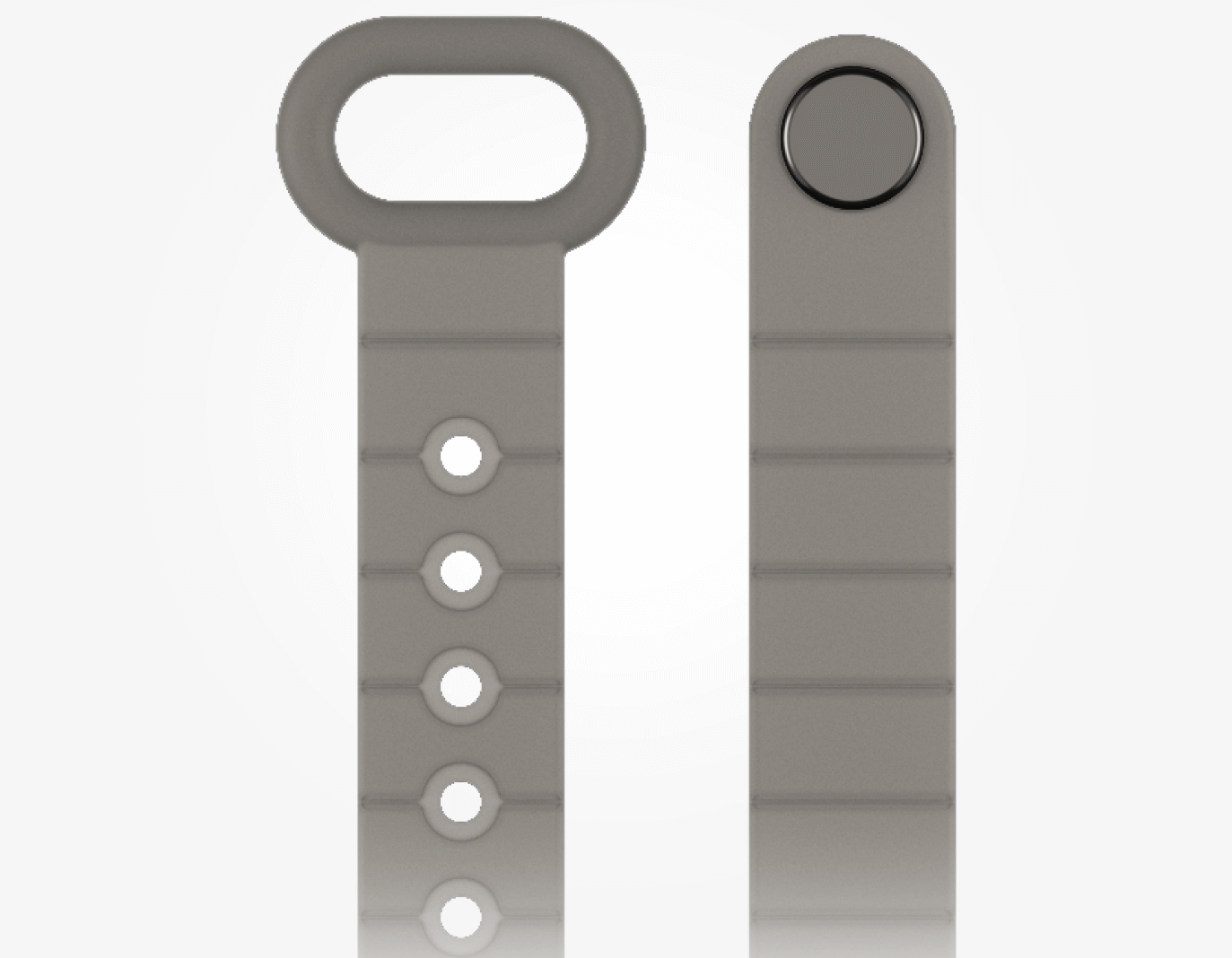

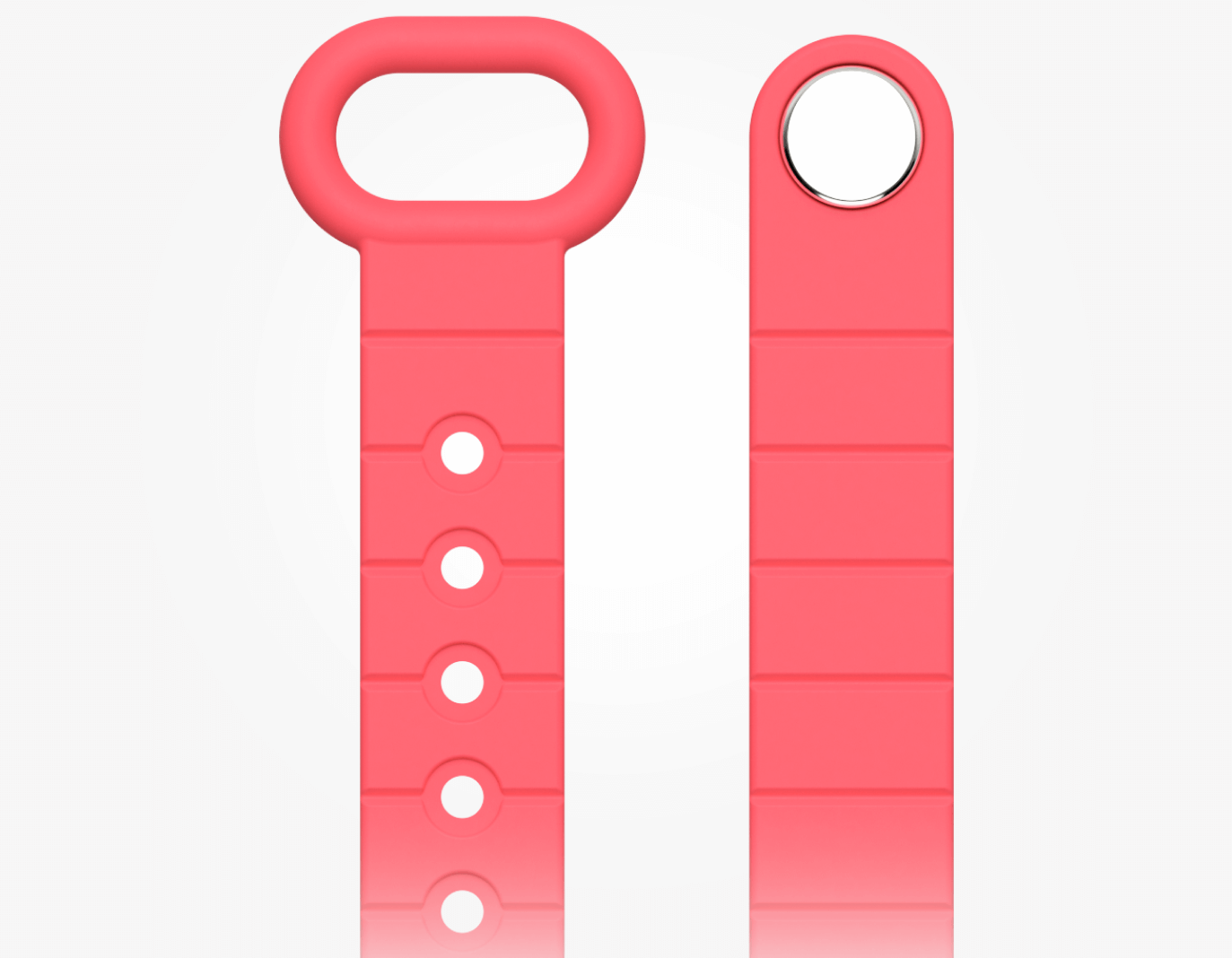

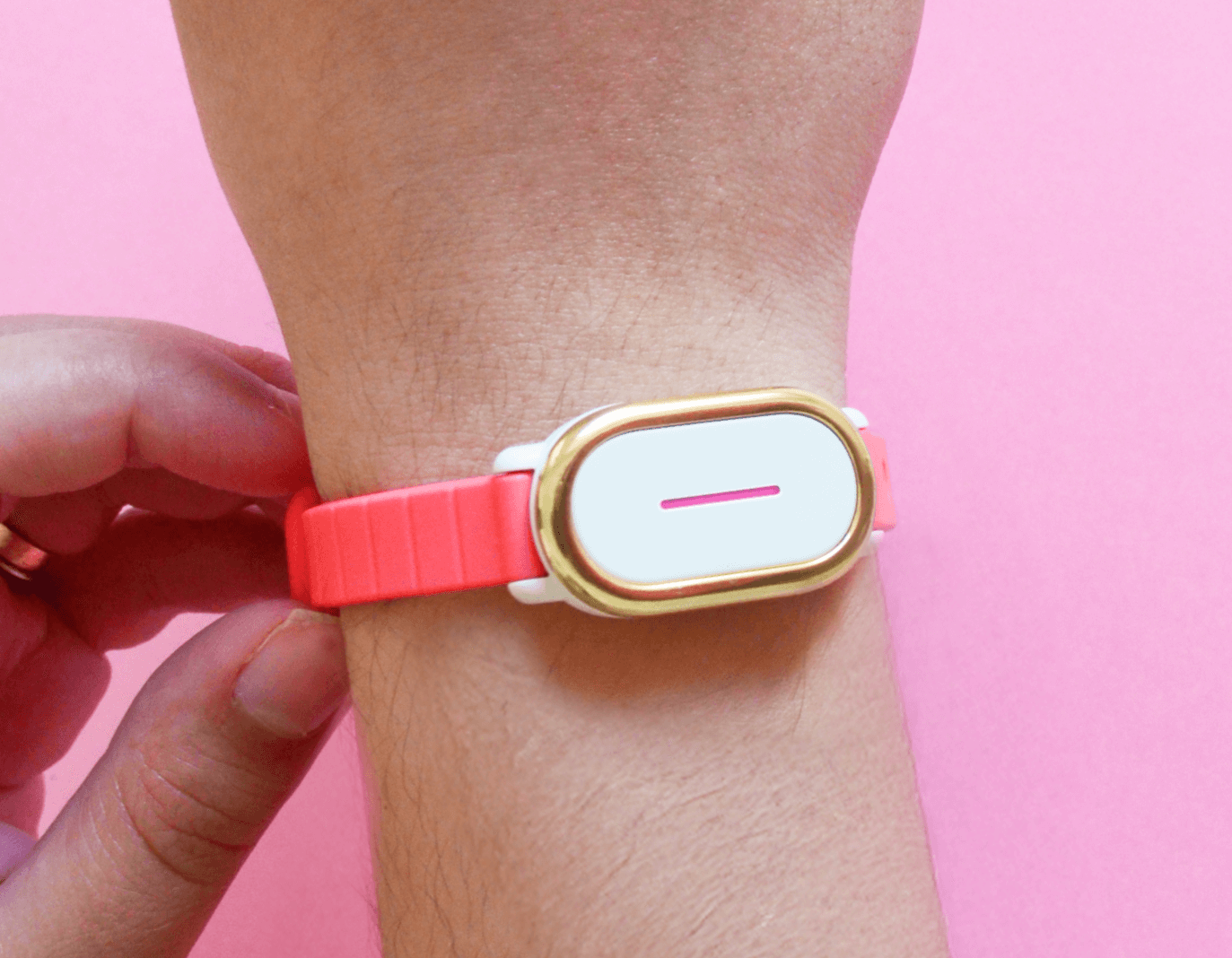

The documentary The Celluloid Closet was one of the first cases of queer codes being talked about to the general public. It explored how even tiny aspects of a person's wardrobe could indicate their queerness to those on the lookout for it. For example, a turquoise and silver bracelet worn on the left wrist was a signal that the person wearing it was a woman-loving woman.

Queer coding nowadays

As queer coding has shifted it’s lost some of its specificity, but it has not lost its use. Today it is things like particular haircuts, cuffed jeans, jewelry choices, and even certain shoe styles can all indicate queerness if you’re on the lookout. And believe me, when you’re queer in a potentially dangerous place, you are on the lookout.

Because of our “secret code,” queer people have always been able to find one another. Especially after instances of collective trauma like what happened with our campus pastor. At that time, people needed us to be there. They needed a place to have a safe community they could mourn and process with.

I don’t want to make it seem like all queer people immediately become best friends or even friends at all. Just like with everyone else there’s a period of test friendship and learning about each other. Queer coding is not some Bat-Signal that immediately connects us with our soulmates. However, it is an integral part of queer culture and often the way that we are able to form safe spaces for ourselves.

On the search for queer joy and community

Queer coding is just one aspect of signals of safety that queer people are constantly on the lookout for. I could probably write a doctorate dissertation on how queer people look and find each other, as well as how we find allies to trust.

More than anything, though, queer people look for a place to be safe and in community. Most often we look for a community with other queer people because they can understand us more acutely than straight/cis people can. Our shared trauma tends to be an override for petty differences.

When I think about who I became close with, it was mostly people who were similarly impacted by the firing of the campus pastor as I was. People who experienced the travesty that the decision caused, and the ripples it had on the community for my remaining years at that institution.

Sharing in a profound experience, whether it be beautiful or devastating still unites people in the experience.

That weight of self and collective trauma is something that makes queer friendships unique. It’s an understanding that can’t be separated from us, for better or worse. We find each other through queer coding, community groups, and other means because at the end of the day we are looking for queer joy and community. Queer friendships shouldn’t be a luxury. They are a necessity. They’re a way to collectively heal and make it through our shared trauma together.

There are few things I’ve experienced like queer joy and it’s a beautiful thing to see.